| This article is incomplete. This article is missing one or more sections. You can help the BirdForum Opus by expanding it. |

Migration

The need for migration

Birds migrate for two main reasons

- To move from areas of decreasing food or water supply to areas of increasing or high availability of food or water.

- To find suitable breeding sites.

The two are often linked, because areas of increased food supply are often in remote areas such as the Arctic Circle where daylight increases in the Summer months to peak at 24 hours a day, ideal to support vast numbers of insects and plants. These remote areas are not very accessible or desirable for human habitation and so provide good natural nesting sites.

Birds are quite resilient to cold and although migrating to avoid it is a factor, it is mainly the decreasing availability of food that drives the migration.

Many migratory birds are juveniles, making the journey for the first time without adult guidance. Some species migrate in different groups; these are defined by age and sex due to feather moult needs, or child rearing methods.

Migration triggers

Different species and even different populations within a species often have different triggers. This is not yet fully understood, but several factors are thought to trigger migration.

- Biological triggers which include hormonal changes and genetic influences which show as inborn ability.

- Changes in day lengths.

- Changes in temperature, which is strongly linked to:

- Weather conditions.

- Availability of food or water.

As changes in day length, temperature and food availability takes place, some species, particularly long distance migrants, have a biological pre-migratory response. Many long distance migrants moult before migration to ensure maximum efficiency of their plumage, as worn and abraided feathers lose efficiency over time. Another part of the preparation is a process known as hyperphagia. It enables them to overeat, thus gaining the fat reserves (hyperlipogenesis) that are needed to survive the journey. Some species only lay down enough fat to reach the next staging post, where they fatten up for the onward journey. Others lay down enough reserves for a non-stop flight. Ruby-throated Hummingbirds can store 40% of their body weight in lipids for the migration across the Gulf of Mexico. It is a critical process, because too much weight takes more energy to get there and too little means starvation on route.

Types of Migration

Migration may be considered not only in terms of length of distance travelled. Some species migrate between the high Arctic and Antarctic. Others travel much shorter distances between their breeding and wintering quarters, but also the methods used to achieve this. These include:

Narrow Front migration

Migratory birds are funnelled into narrow corridors due to topographic conditions, such as coastal strips, river valleys, headlands that shorten water crossings, etc. This causes birds to move from a broad area of migration to a narrow corridor, concentrating migration at points on a flyway, e.g. Falsterbo and the Straits of Gibraltar in Europe, or the Nile Valley and the Rift Valley in Africa. Waders, raptors and storks are examples of the type of birds that are forced into using narrow fronts on their migration.

Broad Front Migration

Migration takes places over a broad front and is not restricted by topographical conditions. Birds depart their breeding sites and fly more or less directly to their wintering grounds over a broad front. Common Sandpiper use a broad front to migrate between Eurasia and Africa.

Parallel Migration

Where birds within geographic groupings of the same species, migrate to areas parallel to other groups of that species. Birds in breeding area A migrate to wintering area WA. Birds in breeding area B move to wintering area WB, etc. This is the case for Common Chaffinch, or Montagu's Harrier. Where the breeding grounds are in Eurasia and wintering areas are in Africa.

Migration Corridors

In some species, the parallel migration has become isolated and separate migration corridors are formed. This is not broad front migration, as the migration corridors are isolated from each other. This is the case for the Barnacle Goose. The birds breeding in Greenland migrate over Iceland to Ireland and northern and western Scotland. Those breeding on Svalbard move to their wintering grounds in northwest England and the group breeding in Novaya Semlya, Siberia and southern Finnland migrate to Estonia, Visby and the Wadden Sea. They do not overlap as a rule and are thus in isolated migration corridors. Obviously some do switch to other wintering sites, but they are the exception to the rule.

Moult Migration

Some species moult their flight feathers before migration. In order to do so, they move to a quiet area nearby that is rich in food and suitable for them to walk between eating, swimming and resting areas. Survival strategies include diving under water, grouping together, or bomb bursting in different directions. All Anatidae moult in this manner. Non-Anatidae species that moult in this way use different strategies, with different distances to their moult sites.

Loop Migration

Birds use a different route for the Spring and Autumn migration. These are influenced by several factors.

Geography and weather conditions: Mountain ranges and bodies of water create natural barriers that channel birds naturally along their length, or to the shortest crossing point, but if the weather conditions are right, certain families of raptors can utilise updrafts and thermals to save energy when travelling in one or both directions. On the opposite leg these conditions may be different and they use a different route. Red-tailed Hawks moving through the Great Lakes use different routes depending on weather conditions. Most birds that were tagged flew between Lake Michigan and Lake Huron in both directions. One tagged bird that flew between Lake Huron and Lake Erie in autumn 2022, flew between Lake Michigan and Lake Huron in Spring 2023. Another flew to the west of lake Michigan in 2022, flew along the eastern shore in spring 2023.

Food availability: some bird species, such as Eleonora's Falcon time their migration to follow swarms of migrating insects . These food sources are not available on return migration, so birds use other factors to decide the route used.

Altitude Migration

Where birds move from one altitude to a lower one and back. Usually, this takes place before winter when food becomes hard to find at higher altitudes, forcing them to move to lower levels. The birds then return when the snows melt. It is normally a mid range movement from one geographical area to another, but it can also occur over short distances when a birds moves down a valley to escape the worst of the snow. Grey Cuckooshrike, Bush Blackcap, Sentinel Rock Thrush and Cape Rockjumper are all examples of altitude migrants.

Leapfrog Migration

Some species including Arctic Tern, Red Knot and Hudsonian Godwit move to the equivalent latitude in the opposite hemisphere on their winter migration, thus leapfrogging shorter range migrants who travel a shorter distance to the equivalent in latitude in the opposite hemisphere.

Drift Migration

High winds, mist or fog may cause migrating birds to be blown off course or lose orientation and fly off course. This is more prevalent during the Autumn migration with juveniles birds undergoing their first migration.

Reverse Migration

Some species of passerines have a gene that causes the first migration in juveniles. Yellow-breasted Bunting. If the gene responsible is faulty, this may cause the birds to fly in completely the wrong direction by 180 degrees.

Delayed migration

The effects of drought can cause delays in the Spring migration from birds leaving their wintering grounds in Africa. Birds that don't have the fat reserves, will not survive migration and need time to gain them. Global warming has caused delays in the Autumn migration for birds leaving their breeding grounds in the high Arctic, as the snow and ice are forming later and later. Young birds can continue feeding on insects that are still active and seeds that are not yet buried under snow and ice. It enables them to delay their migration. There is a higher risk of being caught out in severe weather, or being blown of course during increasingly windy conditions, making delaying the migration a risky strategy. The payoff is the chicks are stronger, have greater fat reserves and are more used to flight.

Prolonged stopovers

Extremely cold weather in Europe causes a prolonged delay in the Spring migration. The birds have to wait until the snow and ice retreats before they can continue with their migration. Loss of suitably large stopover areas cause food shortages. Birds are forced to turn around and fly back to suitable sites if delays are serious enough.

Nomadism

In areas where drought may occur in some years, birds who are otherwise resident, become nomadic, so that their requirement for food or water can be met. Most nomads depend on grass seeds, nectar or invertebrates and usually occur in arid and semi-arid regions. Most of them are small in size. Some raptors are nomadic and follow outbreaks of rodents. Magpie Mannikin, Cut-throat Finch, Red-headed Finch, Black-shouldered Kite, Black-winged Kite.

Birds have several methods by which they can navigate their way across the globe during migration.

The sun's azimuth

It is not the sun's height in the sky that some species use to navigate, but rather it's azimuth, the angle of the sun on the horizon. It has also been discovered that orientation using the sun is learnt early in life imprinting the data in the bird's memory. The circadian rhythm, the bird's inner clock if you like, has also to be synchronised with this.

Light polarisation

Light is polarised when daylight hits particles in the atmosphere and line up in a north/south direction particularly as the sun is setting. This alignment is thought to be seen by birds even when the sun is obscured by cloud.

Magnetic sense

The magnetic field of the Earth has three components: direction, angle and intensity. The direction of this field points to the magnetic North Pole. The angle is the angle between the magnetic field lines and the surface of the Earth. The magnetic field variation around the globe can be used as a map, once the variations are learned by the bird. The intensity of the magnetic field can be used in a similar way to map migration routes.

Scientists believe that there are up to three ways that this works.

- Small iron oxide (magnetite) crystals could provide a compass.

- The magnetic field is seen by the bird’s eye.

- The bird's inner ear, it's sense of balance, enables it to "feel" the magnetic field.

Scientists currently think that birds have a compass in their eyes and a magnetic mapping device in their upper mandible.

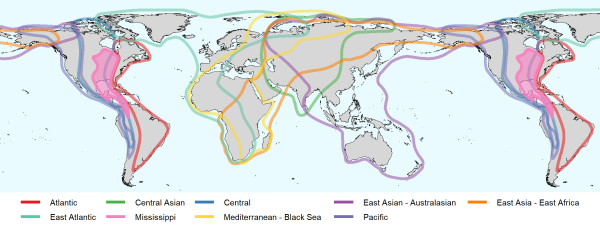

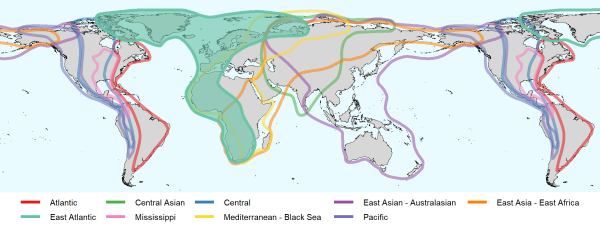

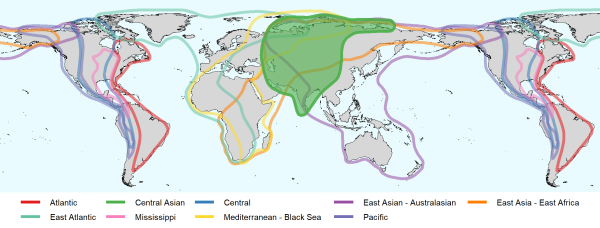

Migration Routes

The main corridors that birds use are known as flyways. Their boundaries are not fixed and different authors recognise slightly different numbers of routes. They also vary somewhat according to the types of birds that are migrating: passerines tend to be more catholic in their choices resulting in them following fewer distinct paths. For example, in North America authorities often distinguish 4 flyways (Pacific, Central, Mississippi, Atlantic) based on movements of raptors and waterfowl. However, these might be better treated as only 3 for passerines [19],[20].

World Flyways

Flyways are pathways that migrating birds utilise on their journeys. Siberia and the northern Americas have Arctic and subarctic breeding grounds which share a common starting point for several flyways.

Birdlife International suggests there are 8 major routes around the world. Other authors may divide these up in slightly different ways. Here we discuss nine global Flyways.

American Flyways

Birds follow three or four main paths when they migrate through the Americas. The four routes we discuss below are based on those suggested by studies of waterbird and raptor migration. Passerines may follow three major paths.

Pacific Flyway

Runs from the Siberian tundra through Alaska in the north down to Tierra del Fuego in the south along the eastern Pacific coastline. Over 300 species are known to use this flyway, including millions of wildfowl, passerines and waders. Stopover points along this route include:

- Copper River Delta, Alaska. Here, up to 1.1 million waders pass though during the peak Spring migration (April 25 – May 15). Vast numbers of Western Sandpiper and Dunlin C. a. pacifica, the most numerous waders of the Pacific Coast, stop here before migrating to their breeding areas. The estuarine mudflats between the barrier islands and the shoreline provide their main source of nourishment in the Gulf of Alaska. Access to these has a major influence on their ability to reproduce further north and west in both Alaska and Siberia. The upland marshes are significant in value for other waders that reproduce there: Short-billed Dowitcher, Least Sandpiper, Greater Yellowlegs, Wilson's Snipe, Red-necked Phalarope, Spotted Sandpiper, Semipalmated Plover and to a lesser extent, Lesser Yellowlegs.

- Fraser River estuary, Canada. These coastal wetlands provide support for over 1.4 million waders including Western Sandpiper; 240,000 waterfowl including Snow Geese and about 4,000 raptors like American Barn Owl, Bald Eagle and Peregrine Falcon. There are 262 bird species, (Jun 2021), in the Delta, 65% are migratory.

- Old Crow Flats, Yukon Territory. up to 300,000 birds nest in this region. They are joined in the post-breeding period by more birds arriving to moult, fatten up and prepare for migration.

- Stikine River Delta, Alaska. This provides food for up to three million migrating birds annually including 14,000 Snow Goose, over 10,000 Sandhill Cranes, up to 164,000 Western Sandpiper and nearly 2000 Bald and Golden Eagles

- Point Reyes National Seashore, California. 38°4′N 122°53′W. 71,028-acre (287.44 km2). Nearly half of the bird species seen in mainland Canada and the USA and 2/3 of wader/shorebird species have been seen at Point Reyes. Point Reyes National Seashore lies at a vital point for wintering birds and passage migrants. A full list of bird species is given on the Point Reyes page.

- Panama. More than one million waders use the Upper Bay to refuel, or overwinter. This includes 165,000 Semipalmated Sandpipers and 30,000 Semipalmated Plovers. Austral migrants also visit Panama during the southern winter. These include Brown-chested Martin, Blue-and-white Swallow and Pearly-breasted Cuckoo. The need for protecting overwintering locations is therefore important during both the southern and northern winters. The pressure on land use for suitable conservation sites effectively doubles.

- Ecuador. Humedales de Pacoa, especially the area between Monteverde and San Pablo is visited by 20-30,000 Wilson's Phalarope that overwinter in the lagoons along the coast. Other neararctic migrants reaching Ecuador include Blackburnian Warbler, Canada Warbler and American Redstart.

- Peru. The Laguna de Ite in southern Peru provides and important wintering site for Elegant Tern. Boreal Common Terns and Elegant Terns also overwinter further north near Mollendo. Peru has 79 boreal and 42 austral regular migrant bird species. In addition a further 20 species migrate regularly from the southern oceans and tropical islands, and 4 species from the Galapagos Archipelago. 7.8 % of all Peru's birds are migratory. Accidentals and rarities make up a further 49 species but these are not included in theses figures.

- Chile. Chiloé Archipelago and Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego About 25,000 North American Hudsonian Godwits and Red Knots migrate to their wintering grounds in the salt marshes of the Chiloé Archipelago and to the Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego's northern shore.

Central Flyway

Starts in the Arctic, moves south through the Great Plains of Canada and the United States of America (USA), the western seaboard of the Gulf of Mexico and southwards to Patagonia. The main endpoints of the flyway are in central Canada and the Gulf coast of Mexico, but some species use it to migrate from the high Arctic to Patagonia. (examples needed). The route narrows along the Platte and Missouri rivers of central and eastern Nebraska, which gives a high species count there.

The following states lie within the flyway: Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, [[Nebraska], South Dakota, and North Dakota. In Canada the flyway comprises the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan and the Northwest Territories

Mississippi Flyway

Over 325 bird species use the Mississippi Flyway, for their round-trip each year from their breeding grounds in Canada and the northern USA to their wintering grounds along the Gulf of Mexico and in Central and South America. It is a corridor comprising the states of Alabama, Arkansas, Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Ohio, Tennessee, Wisconsin and the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Ontario.

Atlantic Flyway

Starting at the Arctic's Baffin Island in the north this flyway stretches ever south to the Caribbean and spans more than 3,000 miles or 4,828 km and includes the USA states of Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Vermont, Virginia, and West Virginia. In Canada, it includes the provinces of Newfoundland, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Prince Edward Island, Quebec and the territory of Nunavut. This flyway also reaches Greenland. It is the eastern most flyway in North America. About 500 species of birds use this flyway.

Birdlife combines the Atlantic with part of the Mississippi Flyway in its "Atlantic Americas" Flyway. This may be appropriate if the focus is passerines or perhaps all bird groups.

Alternative view of routes through the Americas

A) The approach we discuss here source? B) Birdlife International's flyways

© by THE_FERN

Birdlife International identifies three major migration routes through the Americas: the "Atlantic Americas", "Central Americas", and "Pacific Americas" Flyways. The broadly cover the same areas as the four routes we discuss above although details differ. The "Central Americas" route is roughly equivalent to the combination of the "Central" and "Mississippi" Flyways. Birdlife's flyways show that some other routes encompass parts of high latitude North America: the primarily Asian "East Asian - East Africa" and "East Asian - Australasian" Flyways extend to include parts of Alaska. Conversely, the "Pacific Americas" Flyway includes parts of north-eastern Siberia. In the east, the "East Atlantic" Flyway includes Baffin Island.

Austral migration

Austral migrants are species of birds that breed in the temperate areas of South America and move north into areas including the Pantanal the Amazon basin and more rarely, as far as the Caribbean for the Austral Winter and return in the Spring. They include many species of ducks and geese and passerines such as the largest group, the tyrant flycatchers. Brown-chested Martin, Blue-and-white Swallow, Pearly-breasted Cuckoo are among the notable Austral migrants that reach Panama for the southern Winter. Snowy Sheathbill breeds on Antarctic peninsular and islands, migrates to southern South America.

Afro-palearctic Flyways

Birds migrating to Africa take one of three main routes.

East Atlantic Flyway

For boreal breeders, their journey starts at various points in the high Arctic. These include;

- Bylot Island is a migratory bird sanctuary in the Canadian Territory of Nunavut, in the high arctic, next to Baffin Island. Migratory breeding species include; 100,000 Snow Goose, Arctic Tern, Red Knot, Glaucous Gull, Sabine's Gull, American Golden Plover, Black-bellied Plover, Common Ringed Plover, Horned Lark, Long-tailed Jaeger, Northern Wheatear, Pectoral Sandpiper, Ruddy Turnstone, Snow Bunting, White-rumped Sandpiper, King Eider, Long-tailed Duck, Red-throated Loon and Sandhill Crane. 300,000 Thick-billed Murre and 50,000 [Black-legged Kittiwake]] are also key breeding species dispersing to the sea.

- Iceland Iceland provides 121 Important Bird Areas. These involve up to four uses; breeding, staging, moulting and wintering. Several sites are used for all four including Lake Mývatn and Breidafjordur. Passage migrants include; Greater White-fronted Goose A. a. flavirostris, Barnacle Goose, Brant Goose, Red Knot, Sanderling, Ruddy Turnstone, Long-tailed Jaeger, Pomarine Jaeger, Pink-footed Goose, Dunlin and Snow Bunting.

- British Isles Their journey continues to stop over points in Shetland and many overwinter in the British Isles, or continue south along the coast of Scotland to East Anglia on England's east coast before they cross the North Sea. The National Trust have acquired (2023) Sandilands golf course in Lincolnshire and intend to convert it to a wetland reserve. This will help migratory and non-migratory birds, by providing another safe area for them to use on this busy flyway. Work should be finished by 2025.

- Novaya Semlya breeders starting their journey from Novaya Semlya in Siberia, reach the Wadden Sea via the Baltic Sea.

- Olonets Plains in Russia host over 500,000 Greater White-fronted Geese and more than 200,000 Bean Geese.

- Falsterbo Scandinavian birds make the crossing to Denmark funnel through here. about 730,000 Common Chaffinch, 208,000 Common Wood Pigeon, 121,000 Common Starling, 87,000 Common Eider, 38,000 Yellow Wagtail, 32,000 European Greenfinch, 32,000 Eurasian Jackdaw, 27,000 Eurasian Siskin, 24,000 Common Linnet, 22,000 Barn Swallow, 20,000 Eurasian Blue Tit, 19,000 Tree Pipit, 16,000 Eurasian Sparrowhawk, 14,000 Common Buzzard, 9,000 Fieldfare, 8,000 Meadow Pipit, 7,500 Stock Dove, 7,500 Honey Buzzard, 7,500 Brent Goose and 7,100 Rook have been counted on average in autumn between 1973 and 2003 and are the 20 most common species counted at Nabben, south of the lighthouse.

- Wadden Sea. This is a system of tidal mudflats following the coastline from Denmark through Germany to the Netherlands. A series of Islands on the outer edges of the mud provides an outer frame to the Wadden Sea, before dropping off into deeper water. It is at a major cross roads of the eastern and western routes at the northern edge of the East-Atlantic Flyway. The mudflats provide a much needed supply of food for nearly 1,000,000 ground-breeding birds from 31 species that use this UNESCO world heritage site. 41 migratory waterbird species moult here, or transit the flyway through this area. In the milder more recent years, it provides a safe haven for wintering species. Approximate numbers include; 256,000 Eurasian Oystercatcher, 84,000 Black-tailed Godwit, 61,000 Eurasian Wigeon. All of the European and Western Russian populations of the 183,000 Dunlin and nearly all of the over 180,000 dark bellied Brent Goose use the Wadden Sea during their annual migration. The total number of birds that use the area annually reaches roughly 12 million. This makes the Wadden Sea one of the most important areas for water bird species in the world.

- Straits of Gibraltar. One the greatest hurdles for migratory birds to overcome is large bodies of water. The Straights of Gibraltar is the shortest way over the Mediterranean Sea that have to be navigated between the continents of Europe and Africa. In reality, there is a wider corridor that is used. Tarifa may be the closest place to North Africa on the southern Iberian coastline at 14 kilometers, but other places as far away as Sagres in Portugal are also used for arrivals and departures. Wind direction and strength determine whether birds set off or wait for better conditions. The Straits of Gibraltar is probably the best place in Western Europe to see the visible migration (vismig) of up to 30 of soaring species such as raptors and storks. 250,000 - 300,000 raptors and about 150,000 Storks make the crossing each season. Average species counts include; 150,000 White Stork, 4,000 Black Stork, 68,000 Honey Buzzard, for some of the 170,000 spring and 230,000 autumn crossings by Black Kite, different routes are used, 3,300 Egyptian Vulture, 10,000 Griffon Vulture, 18,000 Short-toed Eagle and 26,000 Booted Eagle.

- Banc d'Arguin National Park. Following the West African coastline there are major stopovers or end points at the Banc d'Arguin National Park in Mauritania, where 2.25 million Waders overwinter. Species include; 100,000s Dunlin, Bar-tailed Godwit, Red Knot and Curlew Sandpiper, 10,000s Greater Flamingo, Common Ringed Plover, Common Redshank, Eurasian Curlew, Eurasian Whimbrel and Black-bellied Plover. The 40,000 breeding pairs at this site include; Great White Pelican, Reed Cormorant 3 subspecies, Eurasian Spoonbill P. l. leucorodia and P. l. balsaci, Caspian Tern, Royal Tern, little Tern, Bridled Tern, Gull-billed Tern and Common Tern, Grey-headed Gull, Slender-billed Gull, Lesser Black-backed Gull, the endemic Grey Heron A. c. monicae, Western Reef Heron and Nubian Bustard. Cap Blanc birds include; Ruddy Turnstone, Sandwich Tern and Corncrake.

- Djoudj wetland in Senegal, where 2 million Sand Martins find their wintering quarters. This wetland area of 16,000 hectares, involves a large lake surrounded by ponds, streams and backwaters in the Senegal River delta. It has National Park status as well as being an UNESCO world heritage centre. Due to the completion of the Diama Dam project downstream, the natural flooding found in the rainy season (July to September), no longer occurs naturally. However, controlled flooding is carried out by opening sluice gates during the rains, which simulates the natural process. The area is allowed to dry out during the rest of the year. This National Park plays host to about 365 species of birds, including 120 migrants that use the East Atlantic Flyway. The migrants include; 250,000+ Northern Pintail, 200,000 Ruff and 180,000+ Garganey, all of whom overwinter at Djoudj. Breeding species include; 8,750 White-faced Whistling-Duck, 820 Fulvous Whistling-Duck, 640 Spur-winged Goose and 5,000 Great White Pelican.

- The Bijagós Archipelago in Guinea-Bissau is rated to be the second most important area for Arctic breeding waders in Africa. About one million waders spend their winter in the Bijagós, an area of 10,000 km^2 of land, including 1,600 km^2 of intertidal mudflats and sand banks, 350 km^2 of mangroves and 88 islands. Migratory species include; Whimbrel, Eurasian Oystercatcher, Sanderling, Common Ringed Plover, Common Greenshank, Common Redshank, Red Knot C. c. canutus, Bar-tailed Godwit L. l. lapponica and L. l. taimyrensis, Dunlin C. a. arctica and C. a. schinzii, Common Sandpiper, Curlew Sandpiper, Gull-billed Tern, Sandwich Tern and Yellow Wagtail.

- Southern Africa Distribution south of Central Africa is not yet fully understood in migratory birds. This article uses evidence from field guides to establish migration to this very varied region. Southern Africa is at the tail end of the journey for most of the Paleartic migrants that reach this far south. This article does not include vagrant only species. These include; White Stork, Garganey, Northern Pintail, Northern Shoveler, Osprey, Steppe Eagle, Booted Eagle, Black Kite, European Honey Buzzard, Common Buzzard, Western Marsh Harrier, Pallid Harrier, Montagu's Harrier, Peregrine Falcon, Eleonora's Falcon, Eurasian Hobby, Sooty Falcon summer migrant from northeast Africa and Arabia, Amur Falcon Asian breeding visitor migrating over Indian Ocean to Southern Africa and via Horn of Africa on the return journey, Lesser Kestrel, Corn Crake, Spotted Crake, Crab Plover Breeds in northeast Africa and Arabia, Eurasian Oystercatcher, Black-winged Pratincole, Grey Plover, Common Ringed Plover, Little Ringed Plover, Caspian Plover, Greater Sand Plover, Lesser Sand Plover, Great Snipe, Whimbrel, Eurasian Curlew, Bar-tailed Godwit, Black-tailed Godwit, Common Greenshank, Marsh Sandpiper, Common Redshank, Wood Sandpiper, Green Sandpiper, Common Sandpiper, Terek Sandpiper, Ruddy Turnstone, Ruff, Red Knot, Sanderling, Curlew Sandpiper, Little Stint, Red-necked Phalarope, Red Phalarope, Brown Skua, Pomarine Jaeger, Parasitic Jaeger, Long-tailed Jaeger, Lesser Black-backed Gull, Sabine's Gull Holarctic breeder, Sandwich Tern, Lesser Crested Tern non-breeding visitor to east coast mainly summer, Common Tern, Arctic Tern winters to Antarctic, some remain over austral summer on east coast, Little Tern, Saunders's Tern breeds from Arabian peninsular to Somalia, migrates to coastal Tanzania and Madagascar, Sooty Tern breeds tropical Indian Ocean, Bridled Tern breeds tropical Indian Ocean, White-winged Tern, Black Tern, Common Cuckoo, European Nightjar, Common Swift, European Bee-eater, Blue-cheeked Bee-eater, European Roller, Tree Pipit, Barn Swallow, Western House Martin, Sand Martin, Eurasian Golden Oriole, Thrush Nightingale, Garden Warbler, Common Whitethroat, River Warbler, Willow Warbler, Olive-tree Warbler, Icterine Warbler, Sedge Warbler, Great Reed Warbler, Basra Reed Warbler, Eurasian Reed Warbler, Marsh Warbler, Spotted Flycatcher, Collared Flycatcher, Lesser Grey Shrike and Red-backed Shrike.

- Austral/Intra-African Migration

There are more than 100 austral/intra-African migrants that breed in Southern Africa. Some species are partial migrants and only those migratory elements will be dealt with in this article. Those listed also include intra-African migrants whose austral breeding status in Africa is not yet fully understood and local migrants. These include; Cape Gannet, Reed Cormorant, Greater Flamingo, Lesser Flamingo, African Sacred Ibis, Western Cattle Egret B. ibis, Rufous-bellied Heron, Malagasy Pond Heron, Black-crowned Night-Heron, Dwarf Bittern, Abdim's Stork, Yellow-billed Stork, Woolly-necked Stork, Knob-billed Duck, Wahlberg's Eagle, Ayres's Hawk-Eagle, Black-chested Snake Eagle, Yellow-billed Kite, African Hobby, Rock Kestrel, Red-footed Falcon, Common Quail, Harlequin Quail, Streaky-breasted Flufftail, White-winged Flufftail, Lesser Moorhen, Allen's Gallinule, African Crake, Striped Crake, Ludwig's Bustard, Collared Pratincole, Rock Pratincole, Temminck's Courser, Bronze-winged Courser, African Wattled Lapwing, Black-winged Lapwing, Senegal Lapwing, Kittlitz's Plover, White-fronted Plover, Chestnut-banded Plover, African Skimmer, Great Crested Tern, Antarctic Tern breeds Antarctic, winter migrant to coastal waters of South Africa, Damara Tern, Whiskered Tern, Namaqua Sandgrouse, African Cuckoo, Red-chested Cuckoo, Black Cuckoo, Levaillant's Cuckoo, Jacobin Cuckoo, Thick-billed Cuckoo, Great Spotted Cuckoo, Barred Long-tailed Cuckoo, Diederik Cuckoo, Klaas's Cuckoo, African Emerald Cuckoo, Senegal Coucal, Black Coucal, Rufous-cheeked Nightjar, Fiery-necked Nightjar, Square-tailed Nightjar, Pennant-winged Nightjar, Alpine Swift, African Black Swift, Böhm's Spinetail, Little Swift, Horus Swift, White-rumped Swift, Scarce Swift, African Palm Swift, Narina Trogon, African Pitta, Malachite Kingfisher, African Pygmy Kingfisher, Woodland Kingfisher, Mangrove Kingfisher, Grey-headed Kingfisher, Olive Bee-eater, Southern Carmine Bee-eater, Swallow-tailed Bee-eater, Purple Roller, Broad-billed Roller, Dusky Lark, Grey-backed Sparrow-Lark, African Pipit altitude migrant, Mountain Pipit, Buffy Pipit, Short-tailed Pipit, Yellow-breasted Pipit, Western Yellow Wagtail, Wire-tailed Swallow, White-throated Swallow, Pearl-breasted Swallow, Lesser Striped Swallow, Greater Striped Swallow, Red-breasted Swallow, Mosque Swallow, South African Cliff-Swallow, Grey-rumped Swallow, Blue Swallow, Black Saw-wing, Banded Martin, Brown-throated Martin, Mascarene Martin breeds in Madagascar, winters to coastal lowlands of Mozambique, Black Cuckooshrike, Grey Cuckooshrike altitude migrant, African Golden Oriole, Bush Blackcap altitude migrant, Spotted Ground Thrush, Sentinel Rock Thrush altitude migrant, Cape Rockjumper altitude migrant, Capped Wheatear, African Stonechat altitude migrant out of high parts of range in winter, Red-capped Robin-Chat, Cape Robin-Chat altitude migrant, White-starred Robin altitude migrant in south of range, Grey Penduline Tit, Fan-tailed Grassbird altitude migrant, Barratt's Warbler altitude migrant, Yellow-throated Woodland Warbler inland populations are altitude migrants, African Yellow Warbler, African Reed Warbler, Fiscal Flycatcher, Ashy Flycatcher partial altitude migrant, African Paradise Flycatcher, Blue-mantled Crested Flycatcher partial altitude migrant, White-tailed Crested Flycatcher partial altitude migrant, Fairy Flycatcher local altitude migrant, Violet-backed Starling, Red-billed Buffalo Weaver, Chestnut Weaver, Red-headed Quelea, Cuckoo Finch, Green Twinspot altitude migrant, Drakensberg Siskin altitude migrant and Cinnamon-breasted Bunting.

African Black Oystercatchers do not migrate as adults. Evidence suggests that between 36 - 46% of western birds migrate to nurseries on the Namib coast from central Namibia to southern Angola, a distance of 1500-2000 km from their place of birth. These birds return to where they were born 2-3 years later and then remain sedentary. This is a post-fledgling migration that takes 2-3 years to complete, but it starts every year when breeding has been successful in western birds.

Mediterranean - Black Sea Flyway

For the majority of eastern European and western Siberian breeding migrant passerine species, this is the flyway of choice. Birds travelling this route have to navigate difficult obstacles and are funnelled into bottlenecks on islands or land bridges. Before humans developed the technology to trap, or shoot them, the biggest threats they had to avoid were predators, including avian predators migrating along these very same routes, or changes in weather conditions after the decision to fly was reached. Today apart from trapping and shooting of migratory birds, especially in or around the Mediterranean and Sahel regions, birds also are faced with massive habitat loss both on route and at their destination, due to desertification and man-made changes to land use. Stopovers on route include;

Russian Federation

- Taymyr Peninsular Along the Ob, Yenisei and Gorbita Estuaries on the Kara Sea coastline in Russia, are six Ramsar sites. These wetland areas provide one of the most populous waterbird staging, breeding and moulting habitats in the northern hemisphere. These include; Red-breasted Goose, Lesser White-fronted Goose, Greater White-fronted Goose, Tundra Bean Goose, Eurasian Wigeon, Northern Pintail, Tufted Duck and Temminck's Stint. Bird numbers vary between 500,000 and 2 million as water levels fluctuate. Further upstream along the OB, northeast of Khanty-Mansiysk, the Upper and Lower Dvuobje provides one of the world's richest waterbird habitats, supporting between 500,000 and 3 million endangered migratory waterbirds during the spring migration.

Bulgaria

Turkey

- Bosporus Straits, is a major bottle-neck on the Mediterranean - Black Sea Flyway. It is most noted for the visible migration of raptors and storks. During spring and autumn migrations, Migratory species include; Black Stork, White Stork, Great White Pelican, Osprey, European Honey Buzzard, Black Kite, Egyptian Vulture, Eurasian Griffon Vulture, Black Vulture, Short-toed Snake Eagle, Western Marsh Harrier, Hen Harrier, Pallid Harrier, Montagu's Harrier, Levant Sparrowhawk, Eurasian Sparrowhawk, Eurasian Goshawk, Common Buzzard, Long-legged Buzzard, Lesser Spotted Eagle, Greater Spotted Eagle, Steppe Eagle, Eastern Imperial Eagle, Booted Eagle, Common Kestrel, Lesser Kestrel, Red-footed Falcon and Eurasian Hobby.

Israel Israel is one of the great bottlenecks for migratory birds. They are channelled by the Mediterranean Sea on one side and the Arabian deserts on the other. The Great Rift Valley includes a series of natural faults which created rivers, lakes and wetland areas, providing birds with the sustenance they need to survive the journey through this arid landscape. Most birds will reach Africa either by crossing into Eygpt through the Sinai peninsula, or continuing south to Yemen and crossing the 22 km Bab-al Mandab Strait to Djibouti. The latter, a key raptor crossing point, will be discussed in the section about the East Asia - East Africa Flyway. Stopovers in Israel are mainly centred around the Jordan river valley. They include;

- The Jezre'el Valley, or Yizrael Valley is a fairly recent addition to the bird watching scene. Dominated by the Tishlovit and Kefar Baruch reservoirs, large numbers of migratory raptors can be seen, both passage and wintering waterfowl are also found here. Birds include; Little Grebe, Black-necked Grebe winter, Great Cormorant winter, Great White Pelican passage migrant and winter, Western Cattle Egret, Little Egret, Great Egret winter, Grey Heron, winter, Glossy Ibis passage migrant and winter, Ruddy Shelduck (scarce passage migrant and winter, Common Shelduck winter, Eurasian Wigeon winter, Gadwall passage migrant and winter, Eurasian Teal passage migrant and winter, Mallard passage migrant and winter, Northern Pintail scarce winter, Northern Shoveler passage migrant and winter, Marbled Duck passage migrant and winter, Common Pochard winter, Ferruginous Duck passage migrant and winter, Tufted Duck winter, Red-crested Pochard rare passage migrant and winter, White-headed Duck passage migrant and winter, European Honey Buzzard passage migrant, Black Kite passage migrant and winter, Short-toed Eagle passage migrant, Marsh Harrier passage migrant, Hen Harrier passage migrant, Pallid Harrier passage migrant, Montagu's Harrier passage migrant, Levant Sparrowhawk passage migrant, Steppe Buzzard passage migrant, Lesser Spotted Eagle passage migrant, Greater Spotted Eagle scarce passage migrant, Steppe Eagle scarce passage migrant, Booted Eagle scarce passage migrant, [[Lesser Kestrel] passage migrant, Common Kestrel, Red-footed Falcon passage migrant, Eleonora's Falcon passage migrant, Common Quail passage migrant, Water Rail winter, Spotted Crake passage migrant and winter, Little Crake rare passage migrant, Baillon's Crake passage migrant and winter, Common Moorhen, Eurasian Coot winter, Common Crane passage migrant and winter, Pied Avocet passage migrant and winter, Collared Pratincole scarce passage migrant, Black-winged Pratincole rare passage migrant, Stone Curlew, Spur-winged Plover, Little Stint passage migrant and winter, Temminck's Stint passage migrant and winter, Ruff passage migrant and winter, Jack Snipe passage migrant and winter, Eurasian Curlew passage migrant and winter, Common Redshank winter, Green Sandpiper winter, Common Sandpiper passage migrant and winter, Black-headed Gull passage migrant and winter, Gull-billed Tern rare passage migrant, Black Tern passage migrant, White-winged Black Tern scarce passage migrant, Whiskered Tern scarce passage migrant, Eurasian Collared Dove, Laughing Dove, Little Owl, White-breasted Kingfisher, Pied Kingfisher, Crested Lark, Tawny Pipit passage migrant, Meadow Pipit winter, Pied Wagtail winter, Yellow-vented Bulbul, [[Eurasian Robin] winter, Cetti's Warbler, Graceful Prinia, Savi's Warbler passage migrant, Moustached Warbler, Great Reed Warbler passage migrant, Lesser Grey Shrike scarce passage migrant, Hooded Crow, Common Starling winter, Common Chaffinch, European Goldfinch, Cretzschmar's Bunting passage migrant, Ortolan Bunting passage migrant, Corn Bunting.

- The Hulah Valley lies to the north of the Sea of Galilee. A well established reserve in agricultural land. It comprises of a reservoir, fish-ponds, pools and reed beds. Birds include; Little Grebe, Black-necked Grebe passage migrant and winter, Great Cormorant passage migrant and winter, Pygmy Cormorant, Great White Pelican passage migrant, Little Bittern passage migrant, Black-crowned Night-Heron passage migrant and winter, Squacco Heron passage migrant, Western Cattle Egret passage migrant and winter, Little Egret, Great Egret passage migrant and winter, Grey Heron winter, Purple Heron passage migrant, Black Stork passage migrant and winter, White Stork passage migrant and winter, Glossy Ibis rare winter, Eurasian Spoonbill passage migrant and winter, Greater Flamingo scarce passage migrant and winter, Greater White-fronted Goose rare winter, Ruddy Shelduck passage migrant, Eurasian Wigeon winter, Eurasian Teal passage migrant and winter, Gadwall winter, Mallard passage migrant and winter, Northern Pintail winter, Northern Shoveler passage migrant and winter, Marbled Duck winter, Red-crested Pochard scarce passage migrant and winter, Common Pochard winter, Ferruginous Duck passage migrant and winter, Tufted Duck winter, White-headed Duck winter, European Honey Buzzard passage migrant, Red Kite rare passage migrant, Black Kite passage migrant and winter, White-tailed Eagle rare passage migrant and winter, Griffon Vulture rare winter, Eurasian Black Vulture rare passage migrant and winter, Short-toed Eagle passage migrant, Marsh Harrier, Hen Harrier winter, Pallid Harrier rare passage migrant and winter, Montagu's Harrier passage migrant, Eurasian Sparrowhawk passage migrant and winter, Levant Sparrowhawk passage migrant, Steppe Buzzard passage migrant and winter, Long-legged Buzzard passage migrant, Lesser Spotted Eagle rare passage migrant, Greater Spotted Eagle passage migrant and winter, Steppe Eagle rare passage migrant, Eastern Imperial Eagle passage migrant and winter, Golden Eagle rare winter, Booted Eagle passage migrant, Osprey passage migrant, Common Kestrel, Merlin passage migrant and winter, Saker Falcon rare passage migrant, Peregrine Falcon rare passage migrant and winter, Black Francolin, Common Moorhen, Eurasian Coot winter, Water Rail winter, Little Crake passage migrant and winter, Common Crane passage migrant and winter, Black-winged Stilt, Pied Avocet winter, Kentish Plover, Sociable Plover rare winter, Spur-winged Plover, Northern Lapwing winter, [[Temminck's Stint] passage migrant, Ruff passage migrant and winter, Common Snipe winter, Black-tailed Godwit passage migrant and winter, Eurasian Curlew scarce passage migrant and winter, Common Redshank passage migrant and winter, Marsh Sandpiper passage migrant, Green Sandpiper passage migrant and winter, Common Sandpiper passage migrant and winter, [Pallas's Gull]] passage migrant and winter, Black-headed Gull passage migrant and winter, Armenian Gull passage migrant and winter, Whiskered Tern passage migrant, Rock Dove, Stock Dove winter, Eurasian Collared Dove, Laughing Dove, Great Spotted Cuckoo rare winter, Long-eared Owl passage migrant and winter, Common Swift passage migrant, Little Swift scarce passage migrant, Alpine Swift scarce passage migrant, White-breasted Kingfisher, Common Kingfisher winter, Pied Kingfisher, Eurasian Hoopoe, Calandra Lark, Crested Lark, Eurasian Skylark winter, African Rock Martin, Barn Swallow, Western House Martin passage migrant, Meadow Pipit winter, Red-throated Pipit passage migrant and winter, Water Pipit passage migrant and winter, Western Yellow Wagtail rare summer, White Wagtail passage migrant and winter, Citrine Wagtail rare passage migrant, Grey Wagtail winter, Yellow-vented Bulbul, Eurasian Wren, Dunnock winter, Eurasian Robin winter, Bluethroat passage migrant and winter, Black Redstart winter, Eastern Stonechat passage migrant and winter, Eurasian Blackbird, Cetti's Warbler, Zitting Cisticola, Graceful Prinia, Moustached Warbler, Clamorous Reed Warbler, Marsh Warbler scarce passage migrant, Sardinian Warbler, Garden Warbler passage migrant, Common Chiffchaff passage migrant and winter, Great Tit, Penduline Tit winter, Palestine Sunbird, Common Starling winter, Southern Grey Shrike winter, Eurasian Jackdaw winter, Hooded Crow, House Sparrow, Spanish Sparrow, Common Chaffinch winter, European Serin winter, European Goldfinch, Corn Bunting.

- The Arava Valley is in the desert in Southern Israel and lies to the north of Eilat. The valley is known for it's resident lark species as well as wheatears. Birds include; Little Grebe winter, Purple Heron passage migrant, Eurasian Teal passage migrant and winter, Mallard passage migrant and winter, Garganey passage migrant, Egyptian Vulture passage migrant, Marsh Harrier passage migrant, Eurasian Sparrowhawk passage migrant, Lesser Spotted Eagle passage migrant, Steppe Eagle passage migrant, Eastern Imperial Eagle passage migrant, Osprey passage migrant, Lesser Kestrel passage migrant, Sooty Falcon summer, Barbary Falcon, Sand Partridge, Common Moorhen, Eurasian Coot winter, Cream-coloured Courser, Spur-winged Plover, White-tailed Plover rare passage migrant, Ruff passage migrant and winter, Common Snipe passage migrant and winter, Green Sandpiper passage migrant and winter, Wood Sandpiper winter, Black-headed Gull passage migrant and winter, Lichtenstein's Sandgrouse, Crowned Sandgrouse, Eurasian Collared Dove, Laughing Dove, Common Swift passage migrant, Alpine Swift passage migrant, Common Kingfisher winter, Little Green Bee-eater, Eurasian Hoopoe, Eurasian Wryneck passage migrant, Dunn's Lark, Bar-tailed Desert Lark, Desert Lark, Greater Hoopoe Lark, Thick-billed Lark rare, Bimaculated Lark, Greater Short-toed Lark, Lesser Short-toed Lark, Crested Lark, Oriental Skylark passage migrant and winter, Temminck's Horned Lark, Sand Martin passage migrant, African Rock Martin, Eurasian Crag Martin passage migrant, Barn Swallow passage migrant, Red-rumped Swallow passage migrant, Western House Martin passage migrant, Richard's Pipit passage migrant, Tawny Pipit passage migrant, Red-throated Pipit passage migrant and winter, Western Yellow Wagtail passage migrant, Citrine Wagtail passage migrant, Pied Wagtail passage migrant and winter, Eurasian Robin passage migrant and winter, Common Nightingale passage migrant, Bluethroat passage migrant and winter, Common Redstart passage migrant, Blackstart, European Stonechat passage migrant and winter, Isabelline Wheatear summer, Black-eared Wheatear, Desert Wheatear, Finsch's Wheatear, Red-tailed Wheatear rare passage migrant, Mourning Wheatear, Hooded Wheatear, White-crowned Black Wheatear, Blue Rock Thrush, Scrub Warbler, Graceful Prinia, Eastern Olivaceous Warbler passage migrant, Spectacled Warbler, Sardinian Warbler, Cyprus Warbler winter, Rüppell's Warbler passage migrant, Desert Warbler winter, Arabian Warbler, Orphean Warbler passage migrant, Lesser Whitethroat passage migrant, Blackcap passage migrant and winter, Eastern Bonelli's Warbler passage migrant, Common Chiffchaff passage migrant, Spotted Flycatcher passage migrant, Arabian Babbler, Palestine Sunbird, Southern Grey Shrike, Woodchat Shrike passage migrant, Masked Shrike passage migrant, Brown-necked Raven, Tristram's Starling, House Sparrow, Spanish Sparrow, Dead Sea Sparrow, Rock Sparrow, Pale Rock Sparrow passage migrant, European Goldfinch winter, Common Linnet winter, Desert Finch, Trumpeter Finch, Sinai Rosefinch winter, Cinereous Bunting passage migrant, Cretzschmar's Bunting passage migrant.

The Nile Valley is probably the easiest inland route across the Sahara Desert. (See section 6.1.2 Desert). After leaving the Jordan Valley and entering Egypt via the Sinai, the main migration route is a long the Nile Valley. 3.75 billion birds from 320 species are estimated to enter Subsaharan Africa from the Palearctic each year. Of these, one million are waterbirds.

Egypt

There are six major inland wetland areas in Egypt:

- Bitter Lakes, between Ismailia and Suez in the Ismailia Governorate. There is little known about the avifauna at the Bitter Lakes. Slender-billed Gull is the only species that overwinter in any great number. May breed locally. Little Tern, Kentish Plover and Spur-winged Lapwing all breed locally in smaller numbers.

- Wadi el Natrun, a row of lakes centered around the southern edge of Bir Hooker and lies to the west of Cairo and south of route 75 in the Beihera Governorate. Bird species include; Black Kite, Common Kestrel, Common Quail, Little Crake, Water Rail, Greater Painted-Snipe, Senegal Thick-knee, Kittlitz's Plover, Spur-winged Plover, Little Stint, Laughing Dove, Little Owl, Blue-cheeked Bee-eater, Desert Lark, Crested Lark, Barn Swallow, Pied Wagtail, Graceful Prinia.

- Lake Qarun lies to the northwest of Faiyum and south of the Regional Ring Road in the Faiyum Governorate. The lake, one of the oldest saline lakes in Egypt, and the area to the north, form a nature reserve with Ramsar status. About 88 bird species have been recorded here. In 2010 the waterbird count was over 26,000 birds. Bird species include; Green-winged Teal, Tufted Duck, Eurasian Coot, Western Cattle Egret, Spur-winged Lapwing, Kentish Plover, Little Tern and Slender-billed Gull.

- Wadi el Rayan Lakes which lies southsouthwest of Lake Qurun also in the Faiyum Governorate. The area is an arid desert depression that is below sea level. The two lakes were formed by run off from drainage ditches fed by water from the local area. It is a Ramsar protected site. Significant bird species include; Ferruginous Duck, African Swamphen 100 breeding pairs.

- Lake Nasser lies to the south of the country on the Nile river in the Aswan Governorate. Its water extend south into Sudan. The lake was formed after the High Dam at Aswan was built. The south part of the lake is known as Lake Nubia after the Nubian Valley which it now occupies. Run off from the overflow was divert at Toska to the Western Desert and formed the Toska Lakes. More than 200,000 waterbirds can winter at the lake. Important bird species; Ferruginous Duck, Black-necked Grebe about 5,800 non-breeding, Great White Pelican over 1,000 non-breeding, Tufted Duck over 19,000 non-breeding, Northern Shoveler around 9500 non-breeding. Other bird species include; Common Pochard winter, Eurasian Wigeon winter, Black-headed Gull winter, Egyptian Goose breeding, Red Kite including Yellow-billed Kite breeding, Senegal Thick-knee breeding, Kittlitz's Plover breeding, Spur-winged Lapwing breeding, Crested Lark breeding, Graceful Prinia breeding, African Skimmer breeding, African Pied Wagtail breeding, Yellow-billed Stork summer and Pink-backed Pelican summer.

- The Upper Nile The river has much more stable water levels since the building of the High Dam at Aswan. The Upper Nile between Luxor and Kom Ombo is made up of wetlands that are mainly agricultural with swamp vegetation on the river's banks. In the winter, over 20,000 waterbirds use this strech of the Nile. Most densely above the Isna Barrage. Important bird species include; Ferruginous Duck. Other bird species at Luxor include; Great Cormorant, Little Bittern, Striated Heron, Squacco Heron, Western Cattle Egret, Little Egret, Great White Egret, Grey Heron, Purple Heron, Glossy Ibis, Eurasian Spoonbill, Greater Flamingo, Egyptian Goose, Green-winged Teal, Mallard, Garganey, Northern Shoveler, Marbled Duck, Red-crested Pochard, European Honey Buzzard, Black Kite, Black-shouldered Kite, Short-toed Snake Eagle, Marsh Harrier, Pallid Harrier, Montagu's Harrier, Long-legged Buzzard, Lesser Kestrel, Common Kestrel, Sooty Falcon, Lanner Falcon, Barbary Falcon, Little Crake, African Swamphen, Common Crane, Greater Painted Snipe, Black-winged Stilt, Stone-curlew, Senegal Thick-knee, Cream-coloured Courser, Kentish Plover, Spur-winged Plover, White-tailed Plover, Little Stint, Temminck's Stint, Dunlin, Ruff, Jack Snipe, Common Snipe, Black-tailed Godwit, Spotted Redshank, Common Redshank, Marsh Sandpiper, Common Greenshank, Wood Sandpiper, Common Sandpiper, Whiskered Tern, African Skimmer, Spotted Sandgrouse, Laughing Dove, Namaqua Dove, Great Spotted Cuckoo, Western Barn Owl, Little Owl, Pallid Swift, Pied Kingfisher, African Green Bee-eater, European Roller, Eurasian Hoopoe, Desert Lark, Sand Martin, Rock Martin, Barn Swallow, Red-throated Pipit, Egyptian Yellow Wagtail, Common Bulbul, Bluethroat, Desert Wheatear, Mourning Wheatear, Hooded Wheatear, White-tailed Wheatear, Blue Rock Thrush, Graceful Prinia, Moustached Warbler, Clamorous Reed Warbler, Sardinian Warbler, Nile Valley Sunbird, Masked Shrike, Hooded Crow, Brown-necked Raven, House Sparrow, Spanish Sparrow, Red Avadavat, Trumpeter Finch.

The Nile Valley and delta has additional smaller wetlands throughout the river and delta areas. More are found at oases in the Western Desert.

Coastal wetlands are found along the Mediterranean and Red Sea coastlines. The six main lagoons on the Mediterranen coast are;

- Lake Bardawil is located east of Port Said and north of route 40 in the North Sinai Governorate. The Lagoon borders the Zaranik Protectorate on it's eastern edge. Now connected to the Mediterranean Sea via two man made channels, Lake Bardawil is a hyper-saline lagoon, primarily used for fish production. The lagoon is also one of four Ramsar sites in Egypt. It is noted for it's use as a staging and overwintering point, with about 500,000 bird visiting annually. About 240 bird species have been noted at the lagoon. Significant bird species include; the globally threatened Pallid Harrier and Corn Crake and significant congregations of Great Cormorant between 5,000–30,000 non-breeding, Greater Flamingo about 13,000 non-breeding, Little Tern 1,200 breeding and Kentish Plover 1,900 breeding. Other species include; Great Crested Grebe, Black-necked Grebe, Scopoli's Shearwater, Yelkouan Shearwater, Great White Pelican, Little Bittern, Black-crowned Night Heron, Squacco Heron, Great Egret, Grey Heron, Purple Heron, White Stork, Common Teal, Mallard, Garganey, Northern Shoveler, European Honey Buzzard, Black Kite, Short-toed Snake Eagle, Hen Harrier, Montagu's Harrier, Steppe Buzzard, Long-legged Buzzard, Lesser Spotted Eagle, Steppe Eagle, Red-footed Falcon, Eurasian Hobby, Eleonora's Falcon, Lanner Falcon, Common Quail, Eurasian Coot, Pied Avocet summer, Black-winged Pratincole, Cream-coloured Courser, Greater Sand Plover summer, Grey Plover, Spur-winged Plover summer, White-tailed Plover, Red Knot, Sanderling, Little Stint, Curlew Sandpiper, Dunlin, Broad-billed Sandpiper, Ruff, Black-tailed Godwit, Whimbrel, Eurasian Curlew, Spotted Redshank, Common Redshank, Common Greenshank, Green Sandpiper, Wood Sandpiper, Terek Sandpiper, Common Sandpiper, Ruddy Turnstone, Pomarine Skua rare winter, Arctic Skua rare winter, Long-tailed Skua, Great Black-headed Gull, Mediterranean Gull, Black-headed Gull, Slender-billed Gull summer, Audouin's Gull, Lesser Black-backed Gull including Heuglin's Gull, Yellow-legged Gull including Caspian Gull, Armenian Gull, Sandwich Tern, Whiskered Tern, White-winged Tern, Eurasian Collared Dove, Laughing Dove, European Nightjar, White-breasted Kingfisher, Pied Kingfisher, Eurasian Hoopoe, Eurasian Wryneck, Greater Hoopoe-Lark, Greater Short-toed Lark, Crested Lark, Eurasian Skylark, Meadow Pipit, Red-throated Pipit, Water Pipit, Pied Wagtail, Thrush Nightingale, Eurasian Robin, Bluethroat, Black Redstart, European Stonechat, Isabelline Wheatear, Pied Wheatear, Cyprus Pied Wheatear, Eastern Black-eared Wheatear, Desert Wheatear, Finsch's Wheatear, Olive-tree Warbler, Ruppell's Warbler, Lesser Whitethroat, Orphean Warbler, Barred Warbler, Eurasian Blackcap, Willow Warbler, Red-breasted Flycatcher, Red-backed Shrike, Lesser Grey Shrike, Great Grey Shrike, Common Starling, House Sparrow, Spanish Sparrow, Common Chaffinch, Ortolan Bunting, Cretzschmar's Bunting, Black-headed Bunting.

- Malaha;

- Manzala;

- Burullus;

- Idku;

- Maryut;

The Red Sea coast has wetland habitats comprising of mangroves, mudflats, marine islands and reefs.

The majority of bird migration analysis has been of diurnal studies of raptors, storks and waterbirds. This leaves the movement of the majority of migratory birds, including passerines poorly understood.

The main route south continues though;

Sudan

- Khor Abu Habil Inner Delta is the only natural alluvial fans left in it's original form in Sudan. One of four Ramsar sites in the Country.

South Sudan

- Sudd

Uganda

Kenya

Tanzania

Southern Africa Bird species are discussed in the East Atlantic Flyway section.

East Asia - East Africa Flyway

to be filled with text

Asian Flyways

Central Asian Flyway

to be filled with text

East Asian - Australasian Flyway

The East Asian - Australasian Flyway (EAAF) starts in the high Arctic. On the Asian side it covers a large part of Siberia and reahes as far west as the Ural mountains and Novaya Zemlya in the north. In North America it stretches to the Banks and Victoria Islands in the north and Alaska and the Aleutian Islands. From there it crosses the Pacific Ocean to just south of the Kamchatka Peninsula and just east of Japan through the Northern Mariana Islands and down to the Solomon Islands, New Caledonia, Norfolk Islands and New Zealand. The central Asian boundary follows the Urals, then crosses to the eastern edge of the Plateau of Tibet, the Bay of Bengal, the East coast of India and Sri Lanka. It then crosses the Indian Ocean and skirts south west of Sumatra, Java and the west coast of Australia. The final leg reaches along the southern edge of Australia, Tasmania then across the Tasman Sea to New Zealands southern islands.

50 million water birds use this Flyway each year including 8 million waders. Important stopovers include:

- The lower Moroshechnaya River, Russia. This staging area is a gathering point for 27 wader species including Nordmann's Greenshank and Spoon-billed Sandpiper. In spring, the estuary hosts more than 400,000 birds. Ten species, including Dunlin C. a. kistchinski, Eurasian Oystercatcher and Eastern Curlew breed in the lower Moroshechnaya area. Thousands of Great Knot and Bar-tailed Godwit and hundreds of Eastern Curlew appear in July for the breeding season. At least 100,000 Whimbrel and Bar-tailed Godwit move through the lower Moroshechnaya during late summer and autumn. At least one million waders and 10,000s of wildfowl stage at the river estuary during the autumn journey south.

- Dandong Yalu Jiang, China. This stopover site is in the North of the Yellow Sea. It is of major importance to the EAAF and to the Trans-Pacific Flyway, as this is one of the crossover points between the two. This nature reserve supports about 50 wader species. An estimated 250,000 stage through the site during their northward migration, including Bar-tailed Godwit and Great Knot.

- Chiku Wetlands, Taiwan. These wetlands are of critical importance to the Black-faced Spoonbill. About 350-500 overwinter here. A conservation project stopped the building of an industrial plant and gave the area protected status.

- Inner Deep Bay and Shenzhen River Catchment Area, Hong Kong, China. On the 4th September 1995, the Inner Deep Bay, including the Mai Po Nature Reserve were declared a Ramsar Site. This key area and the Shenzen catchment area is important not only for 20% of the world's Black-faced Spoonbill population and the critically endangered Spoon-billed Sandpiper. 13 of the 26 bird species that can be found here in significant numbers are globally threatened. Habitat is gated intertidal fish and shrimp ponds known as Gei wais and mud flats enclosed with dwarf mangroves. Each Gei wai is drained systematically for long periods during the winter. This refreshes their bounty and provides a continuous food source for the overwintering birds. 17 new species of invertebrates have also been found here.

- Philippines. The Olango Island Wildlife Sanctuary is one of six Ramsar wetlands in the country. This site is surrounded by intertidal coraline sandflats and mangroves with coral reefs and seagrass beds in an area dotted with small islands. The habitat is suitable for both waterbird stopover and overwintering. An Important Bird Area for significant numbers of migratory waterbirds, the sanctuary takes up 5,800 hectares in the southwest of Olango island and coastal area. 48 of the 77 migratory bird species found in the region have been recorded at the sanctuary, including: Asian Dowitcher, Chinese Egret, Bar-tailed Godwit, Common Greenshank, Common Redshank, Common Sandpiper, Curlew Sandpiper, Eurasian Curlew, Far Eastern Curlew, Great Knot, Greater Sand Plover, Grey Plover, Grey-tailed Tattler, Gull-billed Tern, Kentish Plover, Little Egret, Red-necked Stint, Ruddy Turnstone, Striated Heron, Terek Sandpiper, Whimbrel and Whiskered Tern

- Limboto Lake, Sulawesi, Indonesia. There is a poor understanding of the ecology of landbird migration though tropical Asia. Deforestation is a major factor for loss of habitat for overwintering passerines. Deforestation leads to increased sedimentation of the lakes and waterways thoughout Indonesia, affecting waterbird migration. Limboto Lake is one of the 17 critically sedimented lakes in Indonesia. A enviromental birding group has increased awareness, leading to a national agency for cleaning up these lakes. Restoration has begun to restore environments such as Lake Limboto, where 85 bird species occur, 49 of which are migratory. Awareness of the knock on effects of logging and education concerning the use of invasive plant species for fish nuseries by local fishermen will lead to changes in the methods used.

- Papua New Guinea (PNG). The Tonda Wildlife Management Area (TWMA) in southwestern PNG shares a border with the Wasur National Park in Indonesia and the Kakadu National Park in Australia. It has an area of 590,000 Ha, or 2278 square miles. This gives the area protected a total of 1.3 million Ha (131,000 square kilometers), or 50,579.4 square miles. These wetlands provide habitat for over 250 species of migratory and resident waterbird species and as a drought refuge. Most of the world population of Little Curlew stage through the TWMA.

- Australia. Most bird movement in Australia is due to the unavailability of water. The southwest of the Gulf of Carpentaria, Queensland, has several sites for migratory waterbirds. They include: Over 72,000 Great Knot, about 27,000 Black-tailed Godwit and more than 25,000 non-breeding Little Curlew at peak counts. Eighty Mile Beach in Western Australia provides habitat for peak counts of over 2.8 million Oriental Pratincole, around 167,000 ((Great Knot]] and nearly 94,000 Bar-tailed Godwit. 350,000 Red-necked Stint migrate to Southern Australia.

- Passerines and Near-Passerines. Many near- and passerine boreal breeders migrate south into southern Asia. As tracking devices get smaller, small bird movements will be able to be tracked more efficiently giving conservationists a better idea of where to prioritise their efforts. A few that migrate from Fenno-Scandia include; Arctic Warbler, Red-flanked Bluetail and Rustic Bunting. Those migrating from the northern hemisphere to Australia comprise only about 10 species, including; Yellow Wagtail, Fork-tailed Swift, Oriental Cuckoo and the ubiquitous Barn Swallow. Very few reach further than the far north of Australia.

- Austral Migration. Austral breeders generally do not regularly migrate in Australasia (New Guinea, Australia and New Zealand). There are some exceptions.

- Australian species that migrate within the country include;

- Baillon's Crake Z. p. palustris The population that breeds in southern Australia, winters to north.

- Scarlet Myzomela migrates north in the austral autumn and return in the spring using the eastern coastline.

- Yellow-faced Honeyeater also migrates north in the austral autumn, returning in the spring using the eastern seaboard.

- Welcome Swallow H.n. neoxena breeds in south-eastern and eastern Australia, including Tasmania, with some migrating north to north-eastern Australia.

- Tasmanian breeders that cross the Bass Strait include;

- Silvereye Z. l. lateralis breeds in Tasmania and Flinders Island (Bass Strait), winters to coastal eastern Australia.

- Swift Parrot Breeds in Tasmania, winters to south-east mainland Australia.

- Orange-bellied Parrot Breeds in south-western Tasmania, winters to coastal south-eastern Australia.

- New Zealand's breeding migrants that cross the Tasman Sea, include;

- Double-banded Plover

- New Zealand's South Island breeding migrants that cross the Cook Strait include;

- Wrybill Endemic to New Zealand. Breeds in northern river beds on South Island and winters to North Island.

- Black Stilt is restricted during the breeding season to the upper Waitaki Valley, South Island. Small numbers overwinter to North Island.

- Those moving outside Australasia include;

- Shining Bronze Cuckoo C.l. lucidus breeds in New Zealand and winters to northern Melanesia, C.l.plagosus breeds in southern Australia and Tasmania and winters to Queensland and northern Melanesia.

- Australian Pratincole breeds in Australia and winters to southern New Guinea and Greater Sundas.

- Buff-breasted Paradise Kingfisher T. s. sylvia Breeds in northern Queensland and winters to New Guinea.

- Channel-billed Cuckoo S. n. novaehollandiae breeds in northern and eastern Australia and winters to New Guinea, Lesser Sundas, and Moluccas

- Long-tailed Koel Breeds in New Zealand and smaller islands within 100 km of the main islands. Migrates to Oceania, found in non-breeding season in Palau, Carolines and Marshalls through Fiji, Tonga and Samoa to Cook, Society Islands, Marquesas and and Pitcairn Islands. Also on Bismarck Archipelago, Solomons, Vanuatu, Norfolk Island, Lord Howe Island and on various other islands.

- Pacific Koel E. o. subcyanocephalus Breeds northwestern Australia to northwestern Queensland, winters to southern Moluccas. E. o. cyanocephalus Breeds northern Queensland to southern New South Wales, winters to Moluccas.

- Horsfield's Bronze Cuckoo Breeds in Australia including Tasmania. Winters to Java and irregularly beyond (e.g. Singapore)

- Sacred Kingfisher T. s. sanctus Breeds in Australia to the Solomon Islands, winters to New Guinea.

- Rainbow Bee-eater Breeds in Australia, eastern Indonesia and New Guinea. Winters to Northern Australia, Sulawesi, the Banda Arc and New Guinea.

- Australian Pelican Breeds Australia and Tasmania, winters to New Guinea.

- Brush Cuckoo C. v. variolosus (Australian Brush Cuckoo) Breeds northern and eastern Australia, winters to Moluccas and New Guinea

- Torresian Imperial Pigeon The Australian Top End Northern Territories populations are migratory, crossing the Torres Strait from New Guinea in August and departing by April.

- Pied Stilt Breeds from Indonesia to Australia and New Zealand, winters to the Philippines.

- Australian Hobby F. l. longipennis Breeds southwestern and southeastern Australia and Tasmania. It is partially migratory, winters to the Moluccas, New Guinea, and New Britain

- Plumed Egret Australian birds may winter to New Guinea.

Trans-Pacific Flyway

Some references used in this article do not give the trans-Pacific movement of birds a flyway name. For the sake of this article, it is as good a name as any for grouping together the movement of migratory birds through this region.

The flyway goes from the Arctic ocean crossing the Pacific Ocean using several routes described later and on to destinations from between the Tasman Sea between Australia and New Zealand and French Polynesia. Breeding sites occur mainly on route including the Arctic and Sub-Arctic regions of Alaska, Canada, eastern Asia and the Aleutian Islands. Large numbers of remote Pacific islands are in this flyway including the Hawaiian Islands chain, the Northern Mariana Islands, Guam, Marshall Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Palmyra Atoll, Kiribati's Gilbert, Phoenix and Line islands, Solomon Islands, Tuvalu, Samoa, Tonga, Cook Islands, French Polynesia and New Zealand. The Pacific Islands National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) complex is a group of about 50 islands in the Line islands. Wildlife sanctuaries and places of significant biodiversity along these routes include:

- Izembek Lagoon, Alaska. The peninsula lies between the Bering Sea and the Gulf of Alaska: migrants include: Black Brant Goose B. b. nigricans; 150-200,000, nearly all of the Pacific population of Black Brant use this site to moult, fatten up and prepare for the southern migration. About 50,000 remain here for the winter. The number of overwintering geese is increasing with global warming changing migration patterns. Taverner´s Cackling Goose B. h. taverneri, Emperor Goose; 70,000, over half of the world population migrate through Izembek. Steller's Eider; 23,000 birds moult, fatten up and prepare for their southern migration here.

- Hawaiian Islands Chain A string of Central Pacific islands, treated here as stretching from Midway Atoll to the island of Hawaii, or Big Island as it called colloquially.

- Midway Atoll, Pacific. Migatory species include Ruddy Turnstone, Wandering Tattler, Pacific Golden Plover, Bristle-thighed Curlew and Long-billed Dowitcher.

- Kealia Pond, Maui The refuge is a wetland along Kealia Beach in Maalaea Bay in the south west of the island.

- James Campbell NWR, O'ahu. Between the heliport at Turtle Bay and Kahuku.

- Hanalei NWR, Kaua’i. Located south of Princeville on the northern shore. Migratory species include Bristle-thighed Curlew, Pacific Golden-Plover, Northern Shoveler, Northern Pintail and Snow Goose.

- The mudflats of the Suva Peninsular in Fiji has been noted as an Site of National Significance with the southern migration of species including: Wandering Tattler; 1% of the world's population, Short-tailed Shearwater, Cook's Petrel, Ruddy Turnstone, Pacific Golden Plover and Mottled Petrel listed.

Pacific Island stopover and breeding sites include one or more of the following routes used by a number of long distance migrants, including the following species; Bar-tailed Godwit, Bristle-thighed Curlew, Wandering Tattler and Pacific Golden-Plover.

- Evidence suggests that there is a migration route for the Pacific Golden-Plover through Japan, Honshu, the Ogasawara (Bonin) Islands, Iwo Islands to the Northern Mariana Islands (NMI) -splitting to either Yap in the western Federated States of Micronesia and ending in either Palau. Or the NMI over the Marshall Islands, Gilbert, Phoenix and Line Islands of Kiribati and on to French Polynesia. Palau also has migrating birds from south Asia and Australasia.

- A second route, used by the Bar-tailed Godwit and Pacific Golden Plover, crosses from the Gulf of Alaska to the Yellow Sea between China and Korea, but further south across the open ocean than in the East Asia - Australasia Flyway discussed earlier.

- From the Yellow Sea, The Bar-tailed Godwit follows a third route that goes broadly via the Solomon Islands to Vanuatu, New Caledonia, Norfolk Island and ending at New Zealand where they overwinter.

- The fourth route goes from Alaska southwest over the central part of the Hawaiian Islands chain, on to the Marshall Islands, where the Bristle-thighed Curlew overwinters, or goes either northwest to Wake Island, or southeast to the the Gilbert Island group of Kiribati. The Bar-tailed Godwit travels further to Vanatu where it joins the second route. There is also evidence that the Pacific Golden Plover uses this route.

- Route five is a route used by Bristle-thighed Curlew starts from Gulf of Alaska, goes southeast to approximately 50°N, 140°W, then almost due south to French Polynesia.

- Austral Migration Austral breeders are birds that breed in the southern hemisphere. Not many migrate from this general warmer part of the world as the climate allows residence all year around. Species using this flyway include;

- Long-tailed Koel Breeds in New Zealand and smaller islands within 100 km of the main islands. Winters to Palau, Carolines and Marshalls through Fiji, Tonga and Samoa to the Cook Islands, Society Islands, Marquesas Islands and the Pitcairn Islands.

Migration hazards

Predation

Human hunters pose a serious hazard to migratory birds. Those channelled over the Mediterranean Islands of Malta and Cyprus, along the North African coastline and in the Sahel south of the Sahara are at risk from mist net traps. In the USA, hunting is having a major negative effect on populations during migration. Along the East Asian-Australasian Flyway illegal hunting is having an adverse affect to populations of migrating birds.

Man-made obstacles

Power lines and wind farms take a large toll of migrating birds along the flyways each migration period. In North America alone, power lines kill up to 64 million birds a year.

Another 7 million are thought to die in collisions with telecommunications towers.

Approximately 234,000 bird deaths a year are caused by wind turbines. These deaths are for all birds. Not just those on migration. However, the majority of these deaths are from migratory birds, especially song birds which migrate at night.

Most deaths occur during take off and landing where these turbines are next to stop-over sites.

Large buildings have caused large numbers of fatalities to migrating birds. In the USA up to one billion deaths occur anually. In one incident, 1000 birds were killed by a combination of weather conditions, heavy migration and bright lights on just one building in Chicago, Illinois in one night.

In 2021 the State of Illinois passed the Bird Safe Buildings Act, which requires bird safety design to be incorporated for all new and renovated state-owned construction projects.

Road traffic collisions cause an estimated 89 million to 340 million bird deaths annually in the USA.

Desertification

An increase in desertification in the Sahel region south of the Sahara makes it more difficult for birds to find food on route. Recent climate change effects show increased periods of drought throughout many areas of the world, including along migration flyways.

Change of farming methods

Increased use of and change in type of pesticides used have had a massive negative impact of insect populations. Intensification of farming methods have caused severe threats to migrating birds, due to loss of habitat.

Accidental or deliberate introduction of invasive species

Islands in particular, have had huge negative impacts to biodiversity levels by the introduction of new species.

- Domestic cats Felis catus, especially feral populations, hunt for all of their food. Evidence suggests they have caused a reduction in population levels and the extinction, or near extinction of about fourteen percent of island species. This biodiversity loss may have a knock on effect for migrating birds, as the biomes affected have been altered. There is evidence that that migrating birds prioritise sleep on arrival after long flights and face a higher risk of predation. The lack, or reduction of local food sources directly, or indirectly attributable to cat predation reduces food available to passage migrants.

- Rodents, especially rats, notably pacific rats Rattus exulans, ship rats R. rattus and brown rats R. norvegicus and mice either directly or indirectly have caused a reduction in both migratory and non-migratory bird species. Direct predation is usually on eggs or chicks. Indirect interaction is usually on the predation of plant species in direct competition to avian species.

- The decision to import, for example, the common brushtail possum, Trichosurus vulpecula to establish a fur trade in New Zealand has had serious consequences for natural ecosystems. Mainly folivorous, possums are also opportunistic omnivores. They eat every part of a plant including; leaves, fruit, buds, flowers and nectar. competing with endemic birds and reptiles. This significantly affects tree and plant growth. Possums have a greater impact on species such as rātā trees, genus Metrosideros or kamahi Pterophylla racemosa, in direct competition to avian species such as Tui, New Zealand Bellbird and New Zealand Kaka. The Chatham Islands Bellbird is now extint. They also occupy tree cavities for nesting in direct competition birds such as Red-crowned Parakeet and Saddlebacks.

- Stoat Mustela erminea as well as the above mentioned possum, also predate bird eggs and chicks, including that of the Kea.

- Feral livestock, particularly pigs, cattle and goats have had a major impact on island biodiversity through habitat loss, nest damage or herbivory in direct competition to endemic species.

Habitat change at stop over sites

Reduction of and change of usage to stop-over sites also cause loss of life to migratory birds.

Effects of Global Warming

With global warming effects being felt in the Arctic Circle, birds, particularly geese are staying longer and even overwintering in greater numbers. Pressure is increasing on the vegation biomass as more geese are feeding on it, the growth period is changing at a slower rate. Migrating geese are increasingly at risk of failing to reach their breeding grounds in the high Arctic as competition for plant biomass becomes more critical.

Natural Barriers to Migration

Bodies of Water

Mediterranean, Gulf of Mexico

Desert

Crossing large areas of desert like the Sahara will require different strategies.

Direct Flight

This strategy is used where a bird flies non-stop over the whole desert.

Oasis to Oasis

This involves migrants flying at night and resting up during the day. Each leg is between oases where water and food are available.

Flight by night, stop-over by day

Using this method, a bird or flock of birds will fly straight across the desert at night. The birds will not eat and use up the reserves they have laid down premigration, or at previous stop-overs on route. The daylight will be used for resting and conserving energy. Sometimes birds will extend their night flight into the day if conditions, such as a good tail wind, allow.

Gradual movement using vegetated areas

The only routes across the Sahara using this method is by following the Nile river, or taking the coastal route along the west African coastline. The Nile is bordered with vegetation. Either swamp, or a narrow band of farmland. The coastline has as broader belt of sparse desert vegetation along it's route.

Migrating birds may use a combination of these methods. The second and third method are often combined where oases have dried up, or the distance between them is too far for one leg.

Mountain Ranges